The Oldest Travel Guide in the World

Xenophobia and racism in an 880-year-old Camino de Santiago guidebook

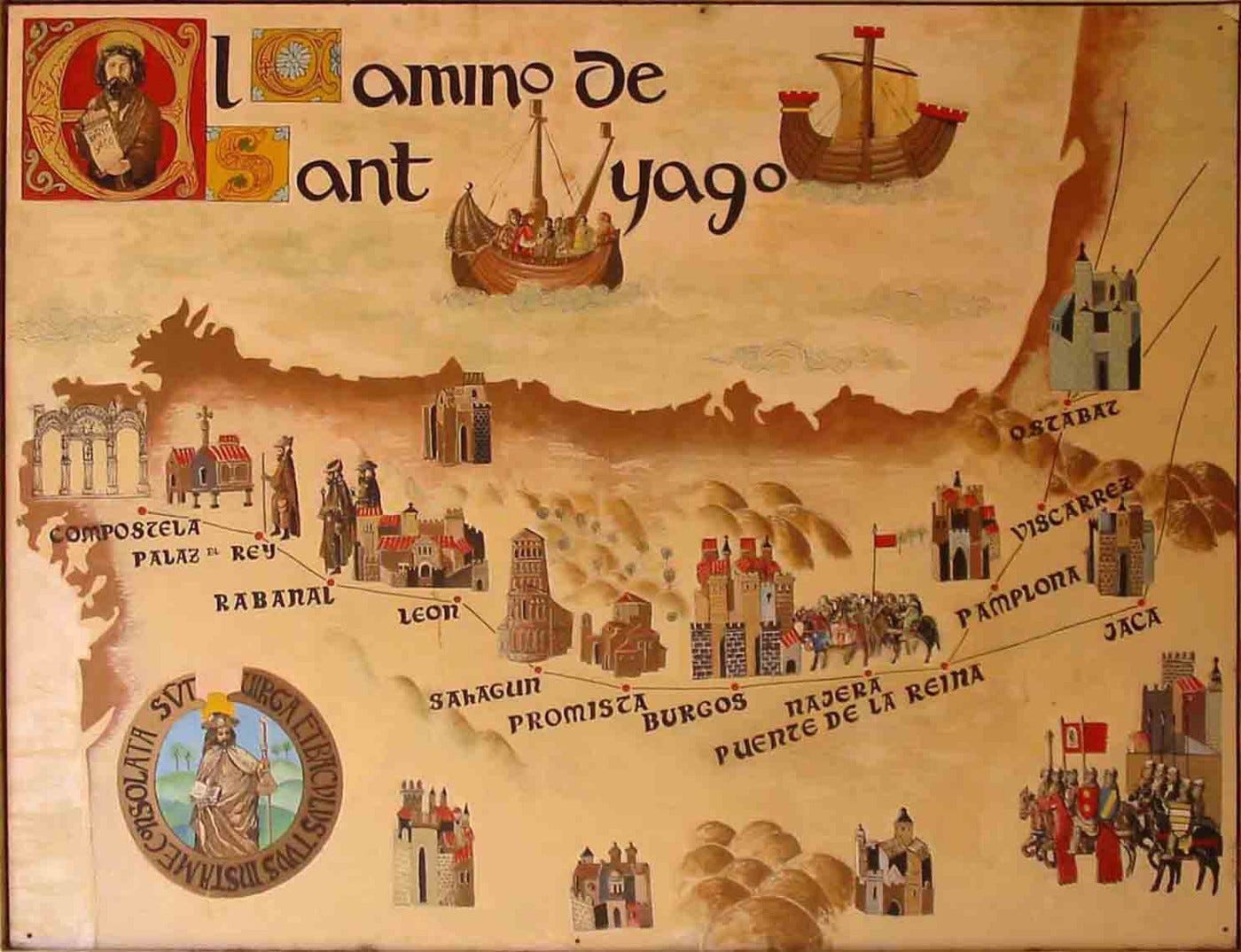

As the Camino de Santiago finally reopens, along with its supporting albergues, hostels, cafés, cathedrals, campgrounds, and monuments, plans are no doubt being hatched by those eager to walk the ancient 500 mile route once again. To plan their journeys, most pilgrims will use one of the plethora of guidebooks written about the camino, but all of these books stand on the shoulders of the original camino guide — the world’s first European travel guidebook and quite possibly the first travel guide ever produced — the 12th century Liber Peregrinationis.

This ancient guidebook is part of the illuminated manuscript also known as the Codex Calixtinus, a richly illustrated set of books created in Santiago de Compostela sometime between 1138 and 1173. Focusing on the apostle St. James and the pilgrimage to his shrine in Compostela, in the northwest of Spain, the books are attributed to Pope Calixtus II, though the book’s real author (or authors) remains a mystery. In 2017, the book was included in UNESCO’s “Memory of the World” register. It has been housed in the archives of the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela for over 850 years, with the exception of July 2011 to August 2012, when it was briefly stolen and then recovered.

Volume V is the practical travel guide section of the work. Compiled between 1135–1140, the suspected author of this volume is a French Benedictine monk named Aymeric Picaud. The book contains all the markers of a modern travel guide with tips such as places of lodging, sanctuaries and relics to visit along the way, and comments on the people and places that make up the route. But one aspect of the book makes it different than modern guidebooks: it’s perhaps the most racist and xenophobic travel guide ever written.

Of Gascony in France, Picaud starts with a complimentary description of the land: “white bread and the best and reddest wine, and plenty of forests, streams, meadows and healthy fountains,” but he clearly detests the people: “Fast-talking, obnoxious, and sex-crazed, they are overfed, poorly-dressed drunks.”

[They] also have sex with their farm animals.

Of the people in Navarre: “[Their] eating and drinking habits are disgusting. The entire family — servant, master, maid, mistress — feed with their hands from one pot in which all the food is mixed together, and swill from one cup, like pigs or dogs. And when they speak, their language sounds so raw, it’s like hearing a dog bark.” If that weren’t enough, they’re also: “perverse, treacherous, corrupt and untrustworthy, obsessed with sex and booze, steeped in violence, wild, savage, condemned and rejected, sour, horrible, and squabbling. [They] also have sex with their farm animals. Moreover, they kiss lasciviously the vaginas of women and of mules.”

Of the Basques, Picaud writes: “The language spoken here is incomprehensible. The terrain is woody and mountainous with a serious shortage of bread, wine and other food supplies, except for plenty of apples and cider and milk.” Not so bad really, considering the insults slung at Navarre.

He describes Galicia as beautiful with plentiful cider on offer and notes: “the Galicians are more like us French people than other Spanish savages, but nevertheless they can be hot-tempered and litigious.”

Today, pilgrims walk the route for all sorts of reasons, from spirituality and health to adventure. A common refrain shared by many pilgrims is the amazing sense of camaraderie they feel on the camino, a truly communal experience that’s rare in the modern world. Professor Olivia Pittet, a four-time camino walker and the author of Camino Made Easy: Confessions of a Parador Pilgrim, is something of a scholar on the ancient guidebook. “The observations about Navarre are particularly biting. I just wonder what Picaud was seeing, and who he was meeting along his camino. I’ve met some shady characters, but no one that has conjugal visits with his donkey.” Pittet goes on: “My three experiences on the camino have been the polar opposite to what the Codex describes. Beautiful people, beautiful food and wine, and friendships that form over the weeks, some ending quickly simply because of geography or walking speed, but others that have lasted a lifetime.”

Today, the typical camino pilgrim is the opposite of xenophobic, says Dr. Matthew Greenhalgh of Brigham Young University, who has walked the camino twice. “People from all over the world — rich and poor, religious and atheist — walk together in harmony. It’s beautiful. It’s ironic that the first guidebook written about this route is so mean. It’s the opposite of the camino experience today.”

And the literature written about (and on) the camino has far surpassed the Codex text in readership. Today, pilgrims are more likely to buy John Brierley’s guidebook, which is now in its 10th edition and has been used by thousands of modern day pilgrims. Luckily, this guidebook is totally free of racism and xenophobia.